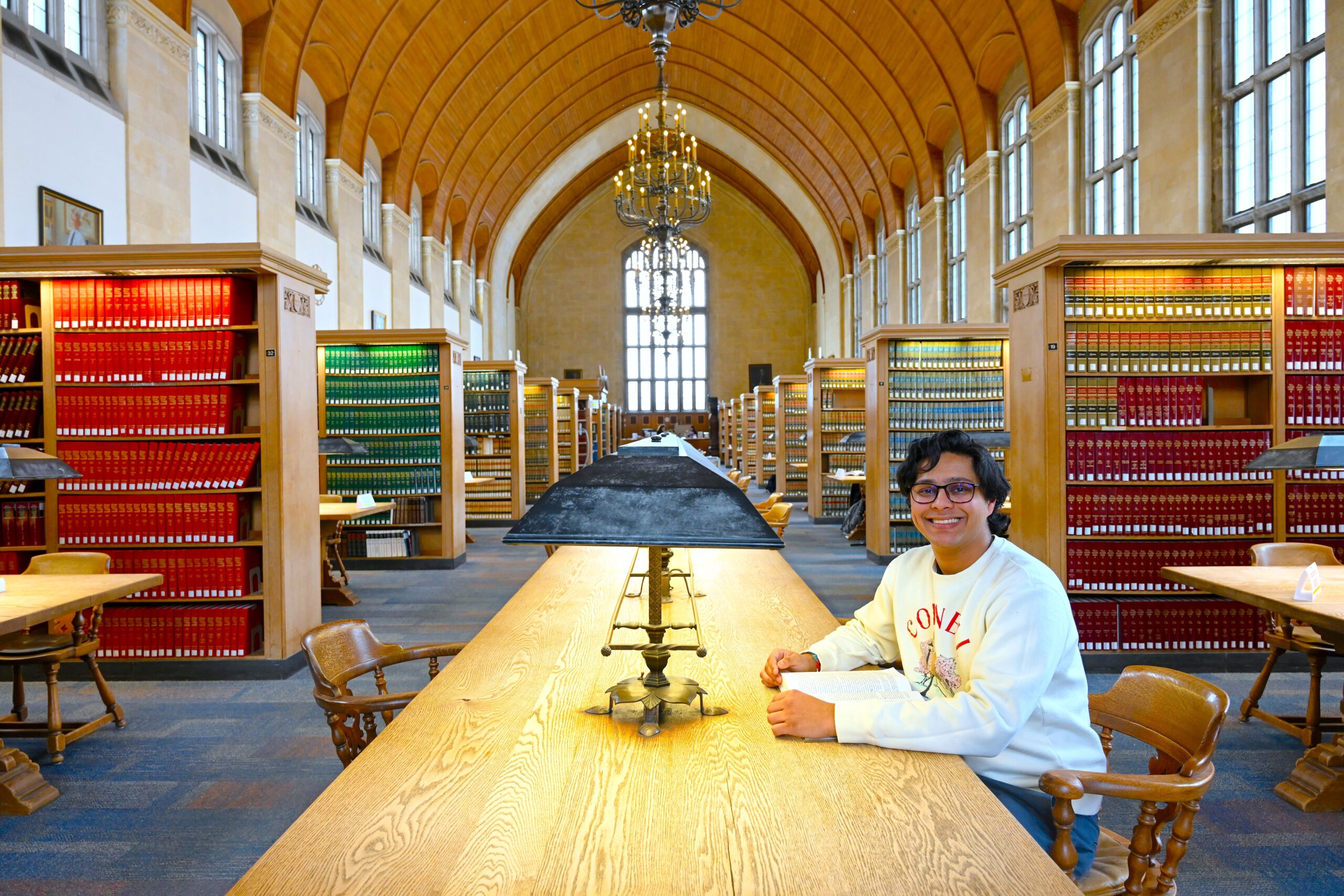

Researchers from Cornell Human Ecology (CHE) and the University of Buffalo discussed the history of Indigenous education — plus modern-day challenges and opportunities — during a panel discussion on Nov. 4 in Mann Library.

The panel, titled “Indigenous Perspectives in Higher Education: Reflecting on the Past to Inform the Future,” was part of the opening of the Cornell University Library exhibit “Redressing Histories of Early Hodinǫ̱hsǫ́:nih Women at Cornell, 1914-1942,” in connection with CHE’s centennial celebrations this year.

The exhibit’s curator, Lynda Xepoleas, Ph.D. ’23, an assistant professor in the School of Fashion Design and Merchandising at Kent State University, moderated the discussion. Panelists were Adam Hoffman, assistant professor in Cornell’s Department of Psychology; Renata Leitão, assistant professor in the Department of Human Centered Design and the American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program at Cornell; and Meredith Alberta Palmer (Tuscarora, Six Nations of Ohswé:ken, Grand River), assistant professor in the Department of Geography and the Department of Indigenous Studies at the University at Buffalo.

Hoffman discussed the psychology of education among Native Americans, beginning with the historical trauma caused by Indian boarding schools, which operated through the 1970s and aimed to eliminate traditional Native American ways of life and assimilate Native American children to Western culture. Today, Native American youth experience higher rates of mental health issues and substance abuse than any other racial or ethnic group and are less likely to complete high school or receive a college degree. In addition to facing structural inequities like underfunded schools, there’s a cultural mismatch, said Hoffman.

“When we think about some of the structural issues, there’s just not congruence between some of the values that are considered important from a Western perspective and an Indigenous perspective,” he said.

In order to address inequities, Hoffman said educators should incorporate community-based, holistic and experiential learning and opportunities to connect with place and acknowledge collective as well as individual achievements, practices that would benefit all students.

Hoffman added that schools need more funding, and students need positive role models and teachers who look like them. Finally, he said that educational institutions like Cornell need to build partnerships with Indigenous communities based on the model of community-based participatory learning. He drew upon his long-standing community-based research partnership with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina.

“We need to be working together to solve problems,” he said. “We are only experts in the phenomenon; we’re not experts in the context. We need to be working with these community partners.”

Leitão, a graphic designer and social design researcher, continued the theme of different ways of knowing in a presentation on epistemic justice. She received her master’s and doctoral degrees from the Université de Montréal, where she worked closely with Anne Marchand, an expert in repairing relationships between institutions and Indigenous communities, and conducted a five-year participatory action research project in collaboration with members of the Atikamekw Nation in Quebec.

“Graphic design is about an essential human power, creating a representation to assess who you are and to influence how others perceive you, how you represent what you know,” she said. She argued that colonialism was not just about possessing land, but also destroying systems of knowledge.

“The Western epistemic canon — that’s what we learn here — became the only valid way to represent the world, so that societies became incapable of representing the world in their own terms.” She said universities should look for ways to recognize and incorporate Indigenous knowledge systems and research priorities.

“I really believe that social justice is about recognizing the value people have, even if it’s different from what you have.” Leitão said. “There is no real social justice without epistemic justice. Our indigenous students deserve to have their ways of knowing valued and respected in the university.”

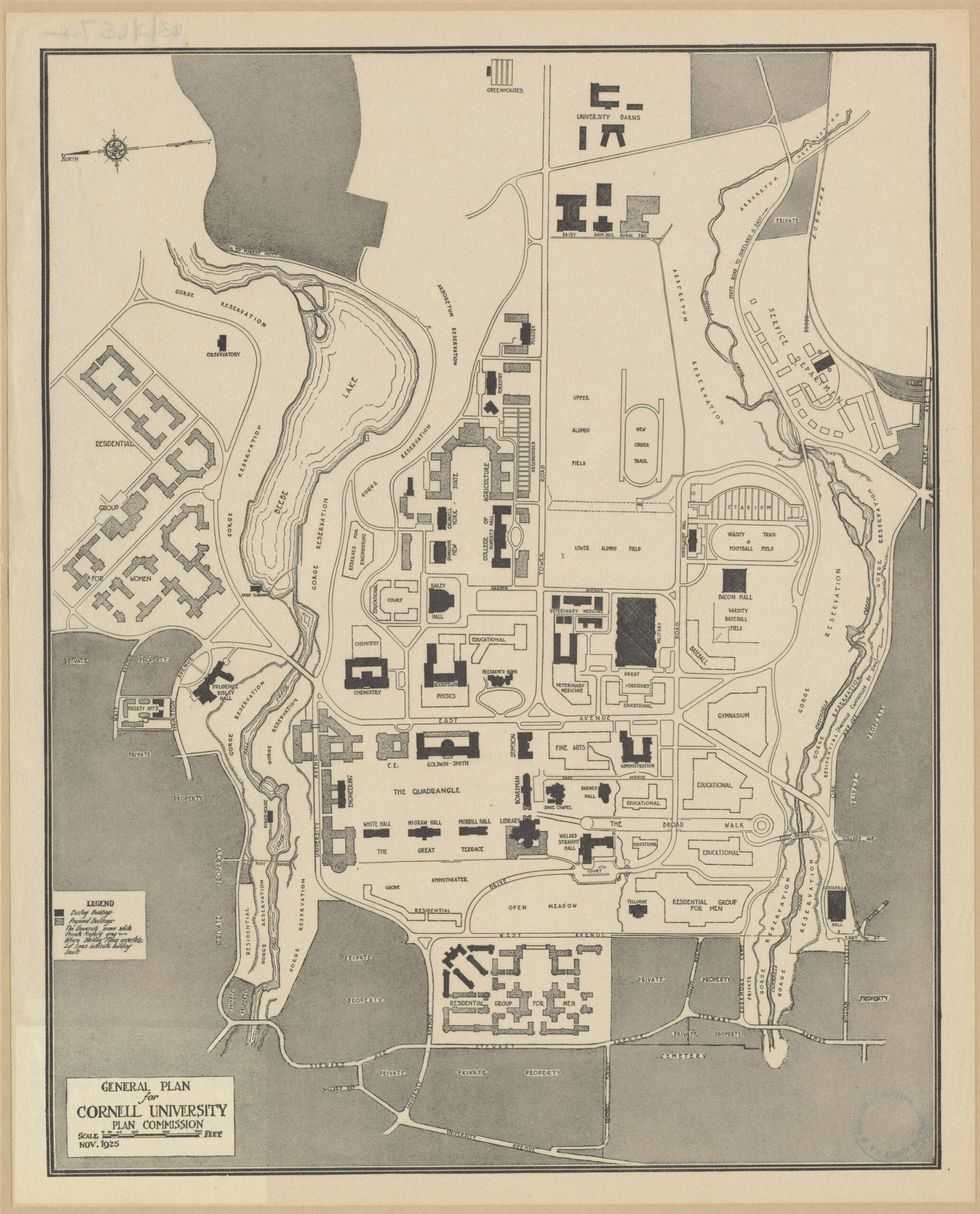

Finally, Palmer, a critical Indigenous geographer, spoke about Cornell’s connection to Native American dispossession and what archives can tell us. Palmer did her undergraduate study at Cornell and received a master’s in public health and a Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, before returning to Cornell as a Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow in 2020. That same year, journalists Robert Lee and Tristan Ahtone published a report in High Country News detailing how the Morrill Act used Indigenous land to fund universities.

The act gave states “public” lands — which had been expropriated from tribal nations — to create colleges to “benefit the agricultural and mechanical arts.” As the most populous state at the time, New York received nearly ten percent of the land allotted by the act, and thanks to Ezra Cornell’s management, Cornell University accrued significantly more financial benefit from the law than any of the 51 other universities.

In response to Lee and Ahtone’s report, faculty in Cornell’s American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program formed a committee to examine the university’s connection to indigenous dispossession. Over the past four years, the committee has identified the Indigenous communities affected by Cornell’s past and present landholding activities and made diplomatic outreach to them. Palmer was part of the committee while she was at Cornell. In 2023, she published “Good Intentions are Not Good Relations: Grounding the Terms of Debt and Redress at Land Grab Universities” in the open-access journal Acme.

Palmer argued that inclusion — bringing more Native American students and scholars to Cornell — is important, but not sufficient.

“Inclusion is not the goal of redress for things such as the 1862 Morrill Act, because the center of Haudenosaunee knowledge and all indigenous knowledge is on the land and with the people,” she said.

Moving beyond inclusion could be accomplished through collaboration as equals, as in the work that Hoffman and Leitão conducted within Indigenous communities, and investment in Native American communities and organizations.

Palmer also discussed the role of archives and what they can tell us, inspired by her work with the Haudenosaunee Archive Resource and Knowledge portal at the University at Buffalo, developed by and for Haudenosaunee people and communities, and Xepoleas’s exhibit.

“We don’t go back in history when we enter archives, even though we may try to find out something about the past,” she said. “They don’t tell us any one truth about the past, but they do offer us new ways to narrate our historic present.”