Widely considered a classic, Clinton Rossiter’s book, “The American Presidency,” has garnered praise from scholars of political science since its publication in 1956. But one of its greatest accolades came directly from the Oval Office, in a personal letter from John F. Kennedy.

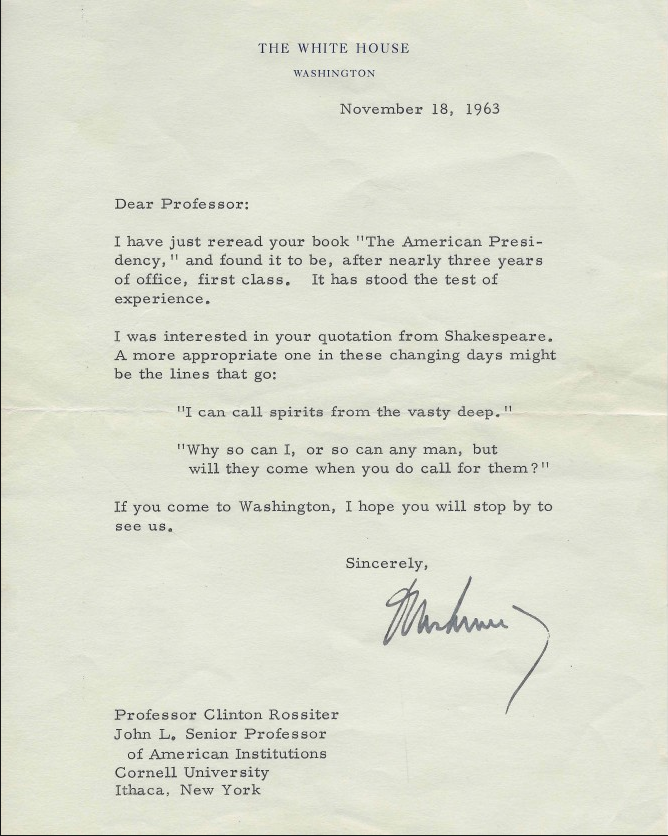

“I have just reread your book … and found it to be, after nearly three years of office, first class. It has stood the test of experience,” Kennedy wrote on Nov. 18, 1963, to Rossiter ’39, who was at the time the John L. Senior Professor of American Institutions at Cornell.

Written on Nov. 18, 1963, JFK’s letter to Clinton Rossiter ended with an invitation to the White House. It is the only known correspondence between the two men, both of whom spent part of their childhood in Bronxville, New York, and also served in the U.S. Navy during World War II.

In his letter—which was recently donated to Cornell University Library by the Rossiter family—Kennedy suggested replacing the book’s epigraph, drawn from Shakespeare’s “Macbeth,” with a quote from Henry IV, which he thought more apt for the political climate testing the powers of his office:

[Glendower:] I can call spirits from the vasty deep.

[Hotspur:] Why, so can I, or so can any man, but

will they come when you do call for them?

The correspondence is remarkable, said Paul Fleming, the Taylor Family Director of the Society for Humanities and chair of the University Faculty Library Board.

“An exchange about Shakespeare in a letter from the president of the United States to a distinguished professor of political science demonstrates the central place the humanities can have in American public life,” Fleming said. “In addition to Kennedy’s erudition, what is striking is his humor or self-deprecation: He counter-proposed an epigraph drawn not from the heaviness of Macbeth, but from Henry IV, Part 1, where Hotspur makes fun of Owen Glendower for his pretensions to control powerful spirits.

“It’s as if Kennedy were poking fun at himself,” Fleming said. “Just because you conjure spirits doesn’t mean they will come.”

Rossiter died in 1970, and the letter—along with a related note from journalist Hugh Sidey—was bequeathed to the library’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections (RMC) by his widow, Mary Ellen Rossiter, MA ’69, who died last October.

“We are very grateful to the Rossiter family for being caretakers of these letters and for making the decision to add them to RMC,” said Evan Fay Earle ’02, MS ’14, the Dr. Peter J. Thaler ’56 Cornell University Archivist.

“We are looking forward to being able to share these with students when teaching with our other political Americana and Shakespeare items,” Earle said. “They also give us an opportunity to educate others on Professor Rossiter’s career.”

David Rossiter ’73, MS ’86, PhD ’88, the eldest of Clinton Rossiter’s three sons, said Kennedy’s letter serves as an artifact of the “changing times” referred to by the president, including the growing civil rights movement in the U.S. and the escalating war in Vietnam.

Clinton Rossiter never got a chance to reply—Kennedy was assassinated four days after writing the letter, on Nov. 22, 1963, in Dallas.

“Our father received the letter the day before Dallas, and he mentioned it the day after Dallas in his memorial speech for Kennedy at Cornell. That was quite poignant,” Winton Rossiter ’78 said.

This story also appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.