An enigmatic figure revered for her otherworldly music, Emahoy Tsege-Mariam Gebru gained a global cult following with the release of her piano album in 2006.

Until her death at age 99 in 2022, Gebru – an Ethiopian pianist, composer and nun who is widely known as Emahoy – also produced a wellspring for fans and scholars of her music: hundreds of pages of manuscripts and home recordings on audio cassettes and reels.

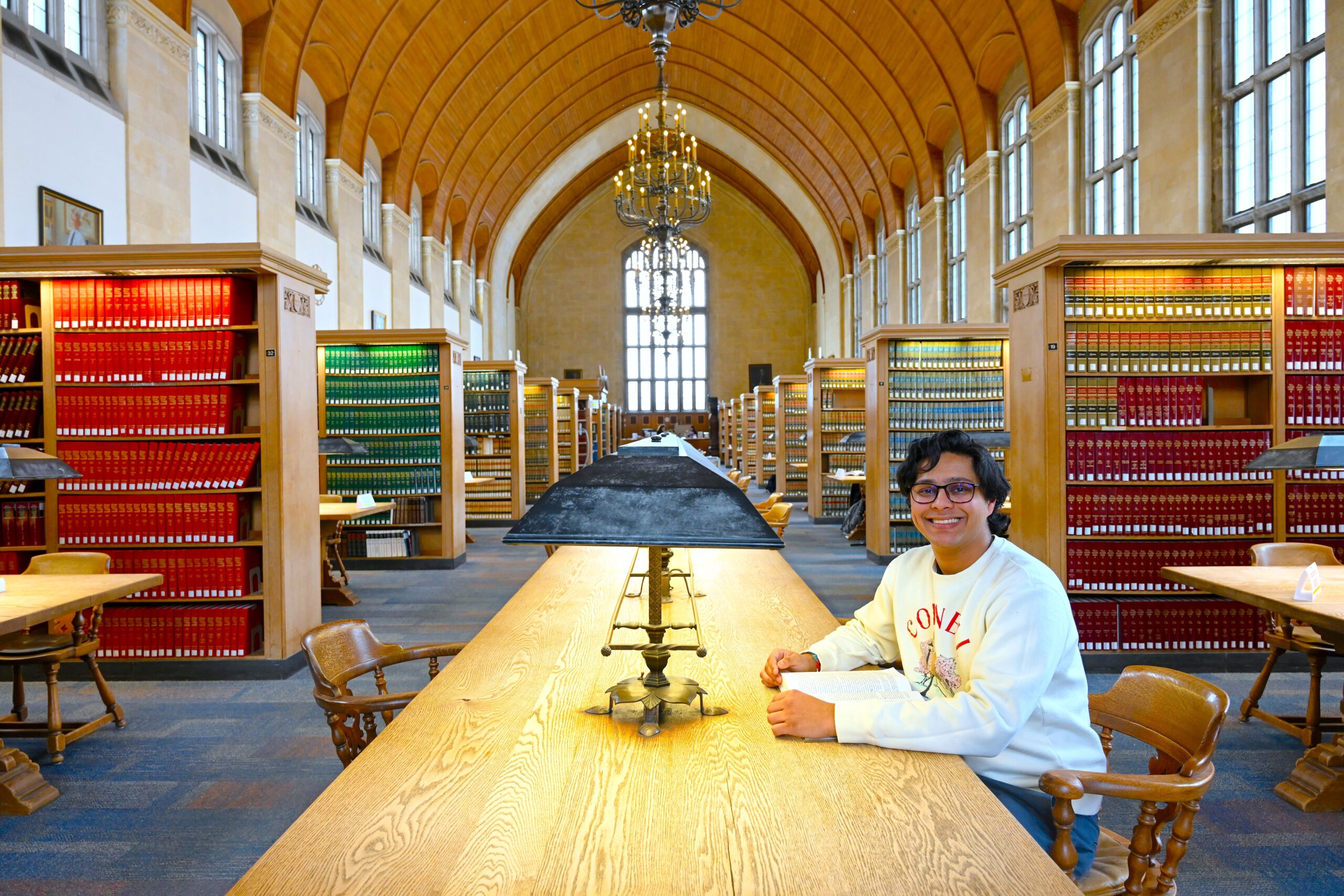

Thomas Feng, a doctoral student in performance practice (keyboard studies), is collaborating with the Emahoy Tsege-Mariam Music Foundation – which has been keeping and digitizing the composer’s archive – to further identify and catalog Emahoy’s written and recorded music. Feng, whose dissertation focuses on the composer’s work, is also helping to digitize a bulk of Emahoy’s home recordings with the aid of Cornell University Library’s Digital Consulting and Production Services (DCAPS).

Alongside Emahoy’s notations, her raw recordings are essential for understanding and performing her music, says Feng, who has done recitals featuring Emahoy’s pieces and who is planning a festival of performances and talks at Cornell in November to celebrate the composer’s life and work.

“The process of how she recorded and rerecorded different performances and drafts has been really interesting for me to see,” he says. “Even a piece of music that made it onto a record was played differently at different times, and that allows for a cross-sectional analysis of how a piece was conceived in her mind, across a period of time.”

Detective work

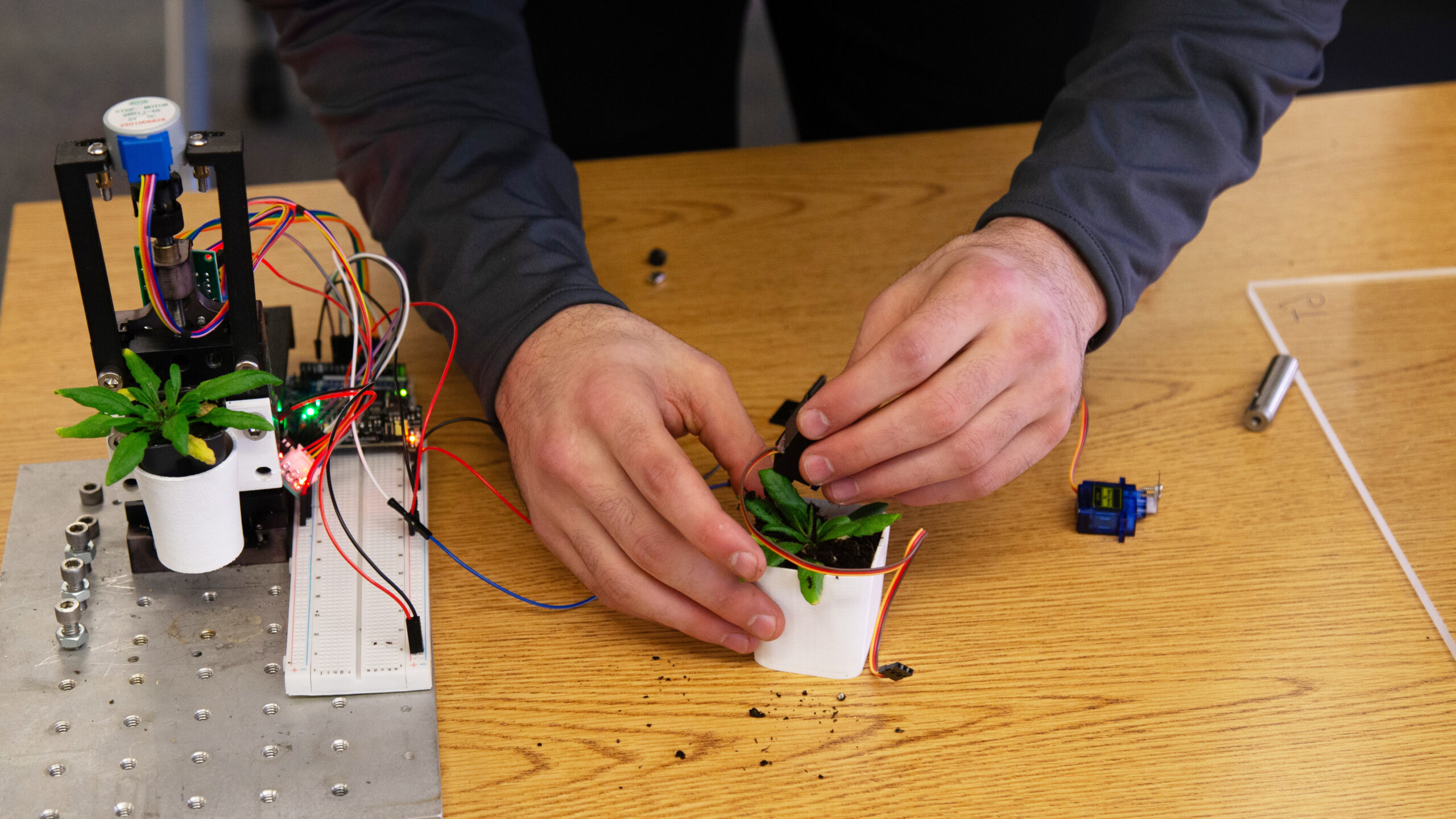

Since the summer of 2022, Feng has been working with DCAPS’s audio engineer Bill McQuay to digitize a batch of Emahoy’s home recordings as faithfully as possible.

“We keep the material in its original state as much as we can while putting it into the digital domain for storage and longevity,” says McQuay, an award-winning sound engineer and technical director who has worked for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and National Public Radio.

This process has involved finely calibrating high-fidelity cassette and reel-to-reel players and sampling the playback using WaveLab, a computer software that’s widely used by archiving institutions.

“We use sample rates that even exceed what humans can perceive, because in the future we don’t know what technologies may be available that will help bring out even more of the detail than we currently can,” McQuay says.

Feng’s expansive knowledge of Emahoy’s oeuvre is vital for the digitization project, says Desiree Alexander, audiovisual collections coordinator for DCAPS. “Thomas really plays a key role because he recognizes the pieces and knows if they’re playing at the right speeds.”

Alexander described how a few of the unlabeled tape reels have proven to be challenging. “There were so many variations on track formats,” she says. “It was real detective work.”

A singular life and music

Political turmoil and exile shaped Emahoy’s life and music.

The pianist-composer was born as Yewubdar Gebru on Dec. 12, 1923, in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa. As a child, she was first exposed to Western classical music at a boarding school in Switzerland where she took violin and piano lessons. When Italy, under dictator Benito Mussolini, invaded and occupied Ethiopia in 1936, she and her politically prominent family were sent to prison camps in Italy. In a monastery where they were forced to stay, Emahoy taught herself how to play the organ. After World War II ended and her family was repatriated, Emahoy pursued music studies with Polish violinist Alexander Kontorowicz in Cairo, Egypt. In her late teens, she returned to Addis Ababa and worked as a secretary in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, while continuing her passion for music.

After a spiritual awakening, she entered the Gishen Maryam monastery, and became a nun at 21, changing her name to Tsege-Mariam and taking on the religious honorific of Emahoy (equivalent to “Sister” for a nun). Fearing religious persecution under a new regime, she emigrated to Jerusalem in 1984 and joined the Debre Genet Ethiopian Orthodox church.

As a writer and translator for the church, Emahoy saved her stipend to produce a CD of her music that was sold at her church for charitable causes. In 1998, Emahoy entrusted her manuscripts and recordings to her niece Hanna Kebbede, who would later establish a foundation in her name. Emahoy’s music first reached a wide audience when Kebbede shared her work with the record label Buda Musique, which had been running a series of compilations on Ethiopian music since the 1990s. In 2006, it devoted “Éthiopiques, Vol. 21” to Emahoy’s music, and the Ethiopian pianist-nun became a cult figure around the world.

A shared goal

“Emahoy’s music speaks to people in a very deep way like no other music I know,” says Cyrus Moussavi, documentary filmmaker and owner of Mississippi Records, who has been working closely with Feng and Kebbede to rerelease old recordings and publish previously unheard pieces by the composer.

“Jerusalem,” a record released by the label in March, includes three tracks that were digitized by Feng and DCAPS from Emahoy’s personal copy of a rare, out-of-print record. More releases, including albums of her vocal and liturgical music, are planned for the next couple of years.

Archival home recordings are especially powerful, Moussavi says. “You hear great artists in conversation with their own work, in their own space, recording on their own time – sometimes for an audience, sometimes as notes for themselves,” he says. “You get a chance to be close to watch the creative process happen, and you have some proximity to greatness when you hear it.”

After Emahoy’s death, Kebbede invited Feng and Moussavi to attend the funeral in Jerusalem. Upon visiting her room at the convent, they made a thrilling discovery.

“We were cataloguing her room, and we found a box of tapes. And I was kind of surprised because I thought I had gone through everything in the room, but there it was,” Kebbede says.

“One of my favorite moments was sitting in the courtyard of the church, going through Emahoy’s tapes,” Moussavi says. “Hanna was reading Emahoy’s handwriting and translating it from Amharic, and Thomas was making very detailed notes of what every single tape says, and I just felt like we were doing right by the music and right by what Emahoy would have wanted.”

At the memorial ceremony, Feng was asked to perform a few of Emahoy’s compositions using the upright piano she played in her room in the convent. The piano keys felt heavy that humid day, Feng remembers, and he had a profound realization.

“For this project, I’ve dealt with different media – tape, vinyl and manuscripts – but then there’s the piano itself, which is also a medium through which a human presence might be felt and remembered,” he says.

After his performance, Feng received compliments from Emahoy’s friends and family as well as from musicians who have studied and performed the composer’s works. But it was an elderly church member’s words that moved Feng the most.

“With you,” he recalls her saying, “Emahoy is not dead.”